Necrosis of teeth can be due to trauma, caries or developmental anomalies. Necrosis of immature permanent teeth poses a treatment challenge. These teeth are not fully formed, have thin dentinal walls which make them prone to fracture and open apices which makes obturation using conventional materials difficult.

For school aged children dental trauma comprises 5% of all injuries for which people seek treatment, and an estimated 25% of school aged children experience dental trauma. Among teeth that have been traumatized, 26.9% of them become necrotic.

"The two main developmental anomalies that may cause necrosis in immature permanent teeth are dens evaginatus and dens invaginatus."

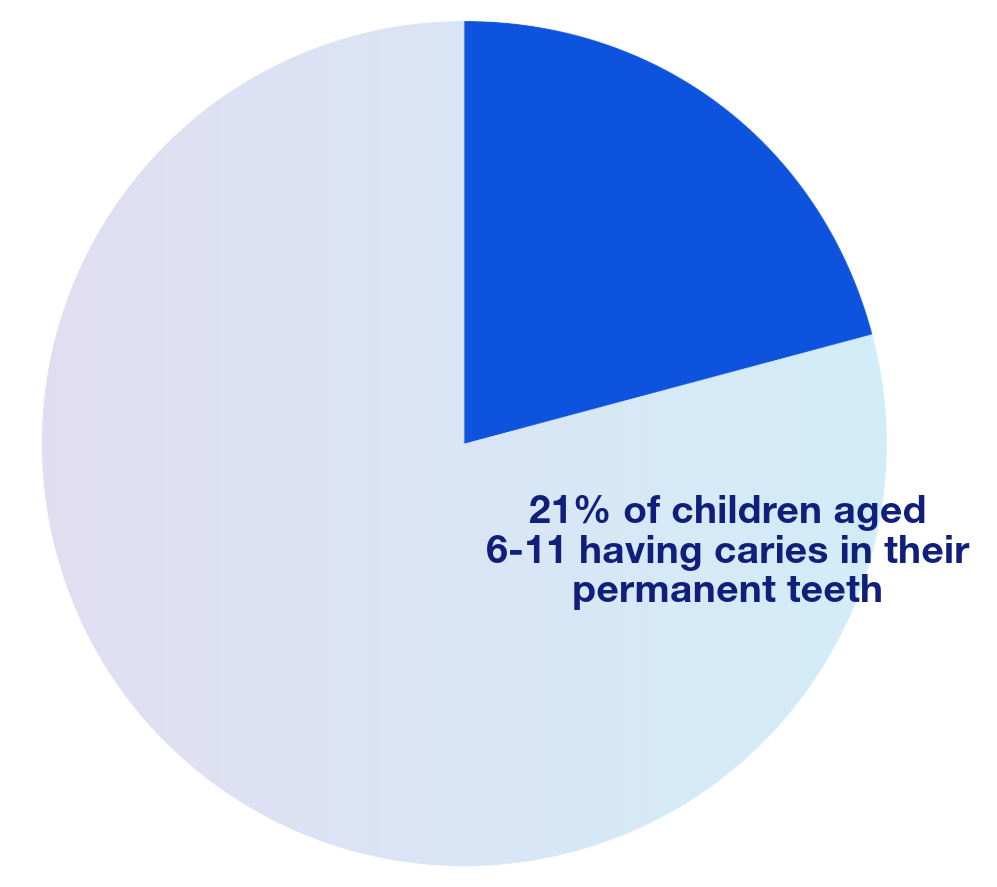

Currently caries is five times more common than asthma and seven times more common than hay fever. Approximately 42% of children aged 2-11 have caries in their primary teeth and 21% of children aged 6-11 have caries in their permanent teeth.

The two main developmental anomalies that may cause necrosis in immature permanent teeth are dens evaginatus and dens invaginatus. Dens evaginatus is an anomalous outgrowth of tooth structure resulting from the folding of the inner enamel epithelium into the stellate reticulum with the projection of structure exhibiting enamel, dentin and pulp tissue. The distinguishing factor between this and other anomalies presenting with supplemental cusps, like the cusp of Carabelli, is the presence of pulp within the cusp itself, which makes the pulp prone to exposure and development of necrosis. This anomaly is generally found on the occlusal surface of posterior teeth or on the lingual surface of anterior teeth. It predominates in Asian populations, Inuit and Native Americans with an incidence of 1-4%. Dens invaginatus is a developmental defect resulting from infolding of the crown before calcification has occurred it may appear clinically as an accentuation of the lingual pit in anterior teeth. In its more severe form, however, it gives a radiographic appearance of a tooth within a tooth (dens in dente). These infolds of the crown can harbor bacteria and predispose the tooth to caries and necrosis. The prevalence of dens invaginatus has been shown to be between 0.3 and 10%. Teeth most frequently presented with dens invaginatus are lateral incisors, followed by maxillary central incisors and more rarely premolar and canines.

Conventional treatment of immature necrotic teeth involves apexification, the induction of a hard tissue barrier across the open apical foramen. Historically the gold standard for apexification was calcium hydroxide therapy. Although this technique produced favorable outcomes there were many drawbacks of this approach. The main drawbacks include decreased fracture resistance due to the long-term use of calcium hydroxide, the length of time for barrier formation, and poor patient compliance.

"Recently, new treatment options have emerged for young immature necrotic teeth. An encompassing term for these treatments is ‘regenerative endodontic therapies’…"

An alternative to calcium hydroxide apexification is mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA)/bioceramic apexification. This approach involves either a one visit treatment where the canals are cleaned and MTA or a bioceramic material is used to create an apical plug in the same visit or a two visit approach where calcium hydroxide is used as an inter-appointment medicament and then at the second visit the apical plug is created. MTA apexification has several advantages over calcium hydroxide apexification, including a reduction in treatment time and decreasing the fracture susceptibility of the tooth.

Recently, new treatment options have emerged for young immature necrotic teeth. An encompassing term for these treatments is ‘regenerative endodontic therapies’, defined by the American Association of Endodontics as a “biologically based procedure designed to physiologically replace damaged tooth structures, including dentin and root structures, as well as cells of the pulp-dentin complex”.

"At the 30-month follow up, radiographic examination confirmed complete closure of the apex and thickening of the root canal walls."

In 2001 a case report was published which revolutionized this field – a 13-year-old patient that presented with a necrotic right mandibular premolar and a sinus tract. Radiographically this tooth had an incompletely formed apex and a periapical radiolucency 10 mm in diameter. Historically, this tooth would have been treated with an apexification procedure, however, in this case regenerative endodontic therapy was attempted. The therapy consisted of irrigation with 5% sodium hypochlorite, followed by 3% hydrogen peroxide and an intra-appointment intracanal medicament and no mechanical debridement. At a future visit a thin layer of calcium hydroxide was placed in the canal and it was permanently restored with glass-ionomer cement and composite resin. At the 30-month follow up, radiographic examination confirmed complete closure of the apex and thickening of the root canal walls. Following this successful procedure there have been many case reports describing similar procedures with differing protocols.

- Preoperative clinical view showing intraoral fistula at the apical gingiva in the mesiobuccal side of tooth 46.

- Preoperative radiography of tooth 45. Incomplete apex formation and periapical radiolucency in tooth 45 were revealed.

- Three-D CT image of involved tooth and its periapical legion taken 15 days after the initial treatment. A periapical legion is expressed as radioopacity by computer image processing.

- Radiography of tooth 45 taken 5 months after the application of calcium hydroxide. Dentin bridge formation is observed.

- Thirty-month postoperative radiography of tooth 45. Completion of the root apex and increase in the thickness of the canal wall was revealed.

© Dental Traumatology 2001; 17: 185–187

Recently, the American Association of Endodontists has proposed a two-appointment approach for treating these immature necrotic teeth. At the first appointment, the tooth is accessed and irrigated with sodium hypochlorite followed by EDTA. This is done without any mechanical instrumentation of the pulp space. Next calcium hydroxide is delivered into the canal space and the tooth is sealed. One to four weeks after the first visit the patient returns, is anesthetized with 3% mepivacaine without a vasoconstrictor, the canal space is irrigated with EDTA and bleeding is induced by over-instrumenting the canal system with a pre-curved K-file 2 mm past the apical foramen. Blood is then allowed to pool and clot to the level of the cemento-enamel junction, a resorbable matrix is placed over the blood clot and a bioceramic material is used as a capping material. Finally, a 3-4 mm layer of glass ionomer is flowed over the MTA to seal the tooth.

More research needs to be conducted in order to fully ascertain the success rate of this procedure, however, it offers another tool in our armamentarium when treating these necrotic immature teeth with open apices.

AAE Clinical Considerations for a Regenerative Procedure, Revised 6-8-16

Ash M. Wheeler’s dental anatomy, physiology and occlusion, 8th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2003;241-2.

Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L. Textbook and Color Atlas of Traumatic Injuries to the Teeth. 4th ed. Oxford, England, Wiley-Blackwell: 2007.

Banchs, F., & Trope, M. (2004). Revascularization of immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis: new treatment protocol? Journal of Endodontics, 30(4), 196-200.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in Oral Health Status – United States 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005; 54:1-44.

Chueh, L.H., & Huang, G.T. (2006). Immature teeth with periradicular periodontitis or abscess undergoing apexogenesis: a paradigm shift. Journal of Endodontics, 32(12), 1205-1213.

Curzon, M.E.J., & Preston, A.J. (1970). Traumatic injuries to the teeth. British Dental Journal, 128(1), 57-59.

Flores, M.T., Andersson, L., Andreasen, J.O., Bakland, L.K., Malmgren, B., Barnett, F., ... & Yates, J.A. (2002). Guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries. II. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dental Traumatology, 18(6), 281-298.

Glendor, U. (2008). Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries—a 12-year review of the literature. Dental Traumatology, 24(6), 603-611.

Hecova, H., Tzigkounakis, V., Merglova, V., & Netolicky, J. (2010). A retrospective study of 889 injured permanent teeth. Dental Traumatology, 26(6), 466-475.

Hülsmann, M., & Hahn, W. (1997). Complications during root canal irrigation--literature review and case reports. International Endodontic Journal, 30(6), 371-385.

Iwaya, S., Ikawa, M., & Kubota, M. (2001). Revascularization of an immature permanent tooth with apical periodontitis and sinus tract. Dental Traumatology, 17(4), 185-187.

Jeeruphan, T., Jantarat, J., Yanpiset, K., Suwannapan, L., Khewsawai, P., & Hargreaves, K.M. (2012). Mahidol study 1: comparison of radiographic and survival outcomes of immature teeth treated with either regenerative endodontic or apexification methods: a retrospective study. Journal of Endodontics, 38(10), 1330-1336.

Jung, I.Y., Lee, S.J., & Hargreaves, K.M. (2008). Biologically based treatment of immature permanent teeth with pulpal necrosis: a case series. Journal of Endodontics, 34(7), 876-887.

Merrill, A.H., & Salinas, M.L. (1964). Study of dental injuries in children. Journal of the American Dental Association, 69(5), 554-558.

Nosrat, A., Li, K.L., Vir, K., Hicks, M.L., & Fouad, A.F. (2013). Is pulp regeneration necessary for root maturation? Journal of Endodontics, 39(10), 1291-1295.

Shah, N., Logani, A., Bhaskar, U., & Aggarwal, V. (2008). Efficacy of revascularization to induce apexification/apexogenesis in infected, nonvital, immature teeth: a pilot clinical study. Journal of Endodontics, 34(8), 919-925.

US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, US Public Health Service. Oral Health in America: Report of the US Surgeon General. NIH publication no. 00-213. Washington, DC: DHHS, NIDCR, USPHS; 2000.

Windley, W., Teixeira, F., Levin, L., Sigurdsson, A., & Trope, M. (2005). Disinfection of immature teeth with a triple antibiotic paste. Journal of Endodontics, 31(6), 439-443.

Yip, H.K., & Smales, R.J. (1974). Review of the management of traumatic injuries to the permanent dentition. Journal of the American Dental Association, 89(6), 364-368.